By Indiana M. A. Humniski

Image Description: The upstairs bay window at Dalnavert Museum, decorated with stained glass depicting a natural scene with floral motifs which are illuminated by the sun. Below the window, a seat is framed with two small cushions on either side and panels of striped wallpapered walls.

Welcome back to Behind the Bookshelf! This is the second of a trio of blog posts that explore different spaces in Dalnavert and link these locations to works of Victorian literature!

In this edition, I invite you to peer through the panes of your imagination to experience a great short story (and perhaps, a ghostly encounter or two!). Dalnavert’s grand bay window is a focal point that demands the attention of visitors. The cushioned window seat would have been a lovely spot for the Macdonalds to sit and dive into a cozy read. After studying the hauntingly perplexing short story “The Library Window,” I believe that its author, Margaret Oliphant, would have found this spot tempting!

If you aren’t familiar with this short story, fear not! You don’t have to have read the literary piece under discussion to enjoy Behind the Bookshelf – but, if you are interested in reading this story, you can read “The Library Window” online.

The Victorian Love of Short Fiction

Victorians were voracious readers of short stories. The Victorian period was a golden hour for this genre. These narratives, particularly those that were serialized in periodicals, were short enough to entertain both working audiences as they commuted home on public transport and upper-class audiences who might have spent the day reading at home. Short stories were cheaper than novels due to their restricted length; they could be passed easily between groups of people, allowing each person to indulge in the pages-long plot then discuss it afterwards.

The Marvellous Mrs. Oliphant (1828-1897)

Margaret Oliphant was a prolific Scottish novelist; she published over one hundred novels and often shared her work under the name “Mrs. Oliphant.” While her prolific production rate has caused critics to question the critical value of her literary work, it is vital to remember that she was a widowed mother of three with numerous other dependents. Determined to support her family, Oliphant turned to writing as her primary source of income. “The Library Window” was the last supernatural tale that Oliphant wrote.

“The Library Window” (1896)

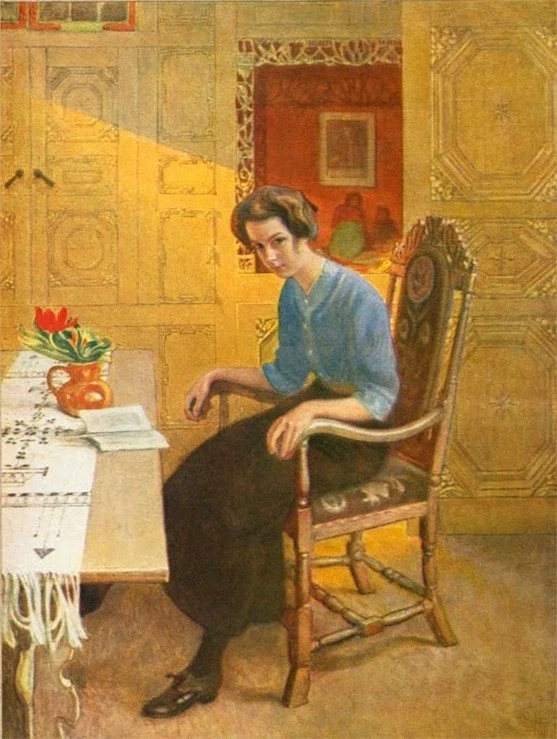

Larsson, Carl. “A Sun Gleam.” 19th century.

The story follows a young female protagonist making a visit to her Aunt’s town home for the summer. While there, she falls into the habit of gazing out the home’s second-story bay window. It isn’t long before she starts seeing the figure of a ghostly scholar in the window of the town’s library, which is located across the street. Not only does this unnamed girl have a love for uncovering the unknown, but she also has a taste for literature. When she isn’t gazing out the window, she spends her time reading (and… eavesdropping).

Even when reading the most interesting book, the things that were being talked about blew in to me; and I heard what the people were saying in the streets as they passed under the window. Aunt Mary always said I could do two or indeed three things at once−−both read and listen, and see. [ …] I did see all sorts of things, though often for a whole half−hour I might never lift my eyes. (2)

The protagonist uses reading as both a means of exploration and an excuse to withdraw herself from social gatherings taking place in the very same room. While burying her nose in a book, she is able to listen in on the conversations of the older women around her.

I had been looking into the room very attentively a little while before, and had made out everything almost clearer than ever; and then had bent my attention again on my book, and read a chapter or two at a most exciting period of the story: and consequently had quite left St Rule's, and the High Street, and the College Library, and was really in a South American forest, almost throttled by the flowery creepers, and treading softly lest I should put my foot on a scorpion or a dangerous snake. At this moment something suddenly calling my attention to the outside, I looked across, and then, with a start, sprang up, for I could not contain myself. (8)

While our protagonist cannot resist the transportive power of her imagination, the window does contain her in the sense that she can only view – and not visit – the hazy interior of the library across the street, where she watches a male student at work. The career-driven and voyeuristic characterization of Oliphant’s young female protagonist both subverts traditional gender roles of female docility and engages the male “peeping tom” stereotype. Not only does she yearn after the scholar’s work space, but she also yearns after him. While her desire to see more of this ghostly male figure can be coded as a sexual awakening of sorts, it is also interesting to imagine her lust for what lies beyond the bay window as a lust for learning. When describing the nearby room, the story’s narrator proclaims:

I saw dimly that it must be a large room, and that the big piece of furniture against the wall was a writing−desk. That in a moment [...] it was quite clear: a large old−fashioned escritoire, standing out into the room: and I knew by the shape of it that it had a great many pigeon−holes and little drawers in the back, and a large table for writing. There was one just like it in my father's library at home. (6)

While she recognizes the function of the furniture quickly, she does not seem to have any personal experience with using a writing desk. And, like the desk with the pigeon-holes, the library in her home is not shared by her but is, interestingly, “[her] father’s library.” Reading in a window seat, remembering her father’s library, and looking longingly into the distant library space, the protagonist is effectively stuck. She is confined by both societal expectations and the architecture of the home’s windows to remain static, looking into libraries instead of occupying them. This reality is made heart-wrenching by the fact that the story’s narrator is an avid reader.

Wealthy Women’s Spaces in Dalnavert

This story’s theme of women’s and girls’ containment in the home is something that the spaces of Dalnavert can help us better understand. The solarium is described by the museum’s virtual tour as follows: “Solariums like this one allowed wealthy women to enjoy the beauty of nature from the comfort of their homes.” Similar to the solarium, the bay window of our female protagonist allows her to imagine an “outside” life. In her case, it is not immersion in the natural world but instead, entry into library and writing spaces that she desires. However, unlike the walls and wide windows of Dalnavert’s solarium, the bay window at Aunt Mary’s feels more like a space of confinement rather than comfort. As opposed to the female servants who would have worked in the house, the wealthier women of Dalnavert might have found some respite in literature while sitting in the solarium. The solarium would also have been, because of its bright light, an ideal setting for needlework, a pastime of leisured women and girls that Oliphant mentions at several points in her story.

As this story was published in 1896, the year after Dalnavert was built, the home’s inhabitants could have read it while living on Carleton Street! Agnes “Gertie” Macdonald, the matriarch of the family, was known for her love of flowers; perhaps, she passed an afternoon or two reading a story by Mrs. Oliphant while surrounded by the botanical beauty of the solarium. Meanwhile, Isabella (called “Daisy”)– the sole daughter of the home – might have sat at Dalnavert’s large stained-glass window on the upper storey, near her bedroom. Perhaps Isabella especially liked the window’s bird designs; her pet parrot might have joined her, a possibility that would have intrigued Oliphant’s adventure-seeking protagonist.

Now that we’ve speculated on the habits of two of the female readers of Dalnavert, let us ask the question: what were women’s reading lives like in the Victorian period?

Womanly Readership in the Nineteenth Century

Given that literacy rates in the English-speaking world rose dramatically in the course of the nineteenth century, it is not surprising that women were diving into literature; however, sexist stereotypes barred some women from reading books with illicit, adventurous, and thrilling themes. The same values guided some people to believe that women should not read the newspaper; instead, their husbands should gauge what he would like to share, if anything at all, to protect women’s nerves.

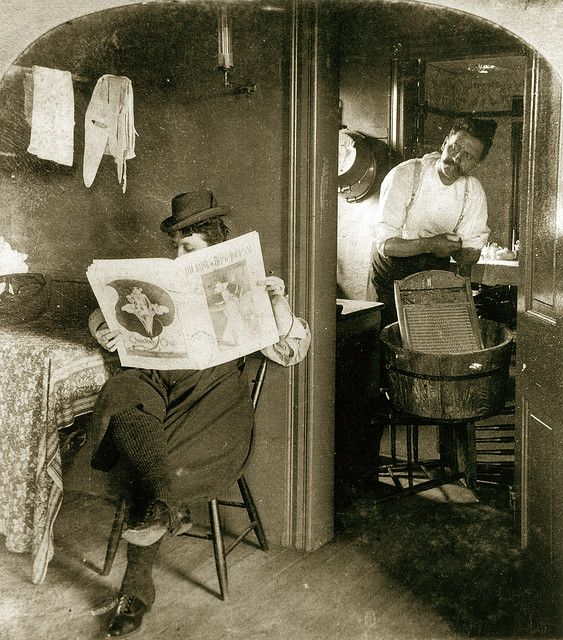

“The ‘New Woman’.” Missouri History Museum, 1899.

This image, housed at the Missouri History Museum, is intended to be satirical; It does, however, show a woman reading a newspaper as something as far-fetched as her wearing pants while her husband washes the dishes.

Contrarily, men reading newspapers is a common theme in Victorian art. Here is a small sampling of Victorian paintings and engravings that feature this commonplace masculine pastime:

The (Male) Noses behind Newspapers

Reading in “The Library Window”

Chase, William Merritt .“The Morning News,” 1886.

It is noteworthy that Oliphant’s story features a woman who enjoys reading newspapers. Aunt Mary’s nightly routine is as deviant to social norms as her niece’s: her niece stares off into the abyss and dreams of accessing male-centric knowledge while her Aunt Mary reads a variety of newspapers. As the story’s protagonist explains,

We had taken a turn in the garden after dinner, and now we had returned to what we called our usual occupations. My aunt was reading. The English post had come in, and she had got her ‘Times,' which was her great diversion. The ‘Scotsman' was her morning reading, but she liked her ‘Times' at night. (4)

Both Aunt Mary and our protagonist are interesting exceptions to the norms of womanly readership in the period. While Aunt Mary shows her desire for knowledge through her twice-daily reading of newspapers, our protagonist shows a similar desire both when she reads fantastical jungle narratives and when she devotes hours to staring at the library window. Oliphant’s persistent showcasing of women’s intellect, whether through newspaper articles or windows, is important. Though of very different ages, these two unmarried women evidently strive for a life beyond sexist stereotypes and censorship, at least, when it comes to their reading habits.

Dashing Back to Dalnavert (and its Desks!)

For our protagonist, the scholar’s desk will remain just out of reach. She is left to admire the desk she sees through the window, a desk reminiscent of her father’s, without being able to engage in a writing career of her own. In Dalnavert, the primary office desk is located in the home’s most masculine room: an office used by Sir Hugh, located on the main floor. Notably, this room is in the same hallway as the female-coded space of the solarium. Like the short story’s scholarly space across the street, the opportunity to make a living and write “like a man” seems to lie just beyond female grasps. Despite this theme running throughout numerous narratives of fiction including “The Library Window” itself, Oliphant’s writing career provides female readers with hope.

Notably, Sir Hugh also had a smaller office area in his dressing-room, a space beside the family’s upstairs bathroom. It is, however, interesting to see the juxtaposition in that small space of, on the one hand, the masculine writing desk and, on the other, the room’s flowery wallpaper. This contrast was frequently commented on during a field trip to the museum I took with my classmates earlier this year. The space is marked by a woman’s decorative touch as flowery wallpapers are conventionally feminine. While Sir Hugh may have used this space to write documents that related primarily to the lives of fellow men – while working as a lawyer, as the Province’s Premier, or as a Magistrate during the General Strike in 1919 – at least a portion of his writing was generated in a place noteworthy for its conventionally feminine design.

Adding to the list of reasons why gender matters to this story is the fact that “The Library Window,” a story about women wanting to write, was written by a woman. Oliphant’s own success, and lifelong use of her own name, instead of a male pen name, is a beacon of hope that shines throughout the short story… almost as brightly as a bold yet fearsome diamond ring that the story's protagonist is fascinated by and eventually inherits.

Overall, “The Library Window” is a short story that would have thrilled audiences of all genders. A word of warning should you feel inspired to read this story yourself: please keep in mind the words of a modern champion of Oliphant’s writing, Merryn Williams, who proposes that, “There is no explanation of the mystery” that is ‘The Library Window.’ Williams is referring here to the story’s suggestion that the scholar in the library is, in fact, a mysterious and vengeful ghost who haunts the women of the protagonist’s family line. While this tantalisingly ambiguous story proposes the possibility of a sexy scholarly ghost, the most fearsome feature of this tale might well be the lack of academic opportunities and career mobility that haunt its female protagonist.

About Indiana M. A. Humniski

Indiana Humniski is a fourth-year Honours English student at the University of Manitoba. She is spending her summer as a Research Assistant focusing on the Victorian period. From studying ghost stories to experimenting with Victorian-era crafting practices, Indiana appreciates the treasures of our literary past and finds great joy in transposing them into her academic future.

Acknowledgements & Sources

Source Citations

“Agnes ‘Gertie’.” Dalnavert Museum, 2014, www.friendsofdalnavert.ca/agnes-gertie.

“Isabella ‘Daisy’ Mary” Dalnavert Museum, 2014, https://www.friendsofdalnavert.ca/isabella-daisy.

“MACDONALD, Sir HUGH JOHN – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 2024, www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=8255.

“Margaret Oliphant.” BBC, 2024, www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/profiles/4M7MyR1wy30hqfTY2HQzCXz/margaret-oliphant.

Oliphant, Margaret. The Library Window. Edinburgh, Blackwood’s Magazine, 1896.

Williams, Merryn. “Margaret Oliphant: A Critical Biography.” St. Martin’s Press, pp. 177-8, https://archive.org/details/MargaretOliphantACriticalBiography/page/n199/mode/2up?q=%22The+Library+Window%22.

Image Citations

“The ‘New Woman’.” Missouri History Museum, 1899. https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/digitool%3A100237.

Chase, William Merritt .“The Morning News,” 1886. https://www.wikiart.org/en/william-merritt-chase/the-morning-news.

Larsson, Carl. “A Sun Gleam.” 19th century.https://books0977.tumblr.com/post/85541549037/a-sun-gleam-carl-larsson-swedish-1853-1919