By Drew Cruikshank, Intern

One of the things that many people cannot wrap their heads around is the Victorians odd obsession with death and mourning—what made mummies, death photography, and our topic of today, taxidermy so fascinating. Well, first, we will need to understand how the Victorians viewed death. There was a definite shift in ideology from the Georgian era into the Victorian era. While rationalism marked the Georgian era, the Victorians’ views aligned more-so with the Romantics, who were intrigued by mysticism. Meaning that, although the Victorian era was a time of technological advancement and progress, culturally, the Victorians were prone to believe in the supernatural.

Taxidermy is the practice of preserving, sometimes stuffing, and mounting deceased animals. When a human family member passed away, they would receive quite an extensive mourning ceremony. When a family pet passed away, however, it was common to hire a taxidermist to preserve the animal, giving them a ‘second life.’ As Sarah Amato mentions in her chapter, “Dead Things: The Afterlives of Animals,” this “reflected the Victorian and Edwardian belief that animals should be useful to humans, even in death.”[1] Although the animal could no longer offer companionship, at least the family could use the taxidermized pet to swank-up their parlour. In an odd way, taxidermy was a tender attempt by the family to immortalize their pet.

For an example closer to home, quite literally, when Lady Macdonald’s pug passed away, she hired a taxidermist to have him stuffed. He then sat in a small wooden cage in the parlour until she sold him at an auction for 50 cents (so, if anyone has a dusty stuffed pug hidden away in their attic or basement, we are on the hunt for one).

While taxidermy was, on one hand, a way to memorialize, or immortalize, your beloved, deceased pets, the Victorians also viewed it as an artform. There were many amateur taxidermists (from the above newspaper clipping, Lady Macdonald’s pug clearly deserved someone with a little bit more expertise), but only a few were able to make a career out of it.

One of the few was Walter Potter. Born in 1835, Potter was an English taxidermist known for his anthropomorphic dioramas of animals mimicking real-life situations. Transfixed by Hermann Ploucquet’s tableaux, a German taxidermist with a similar style, after visiting the Great Exhibition of 1851, a young Potter began creating his own pieces.

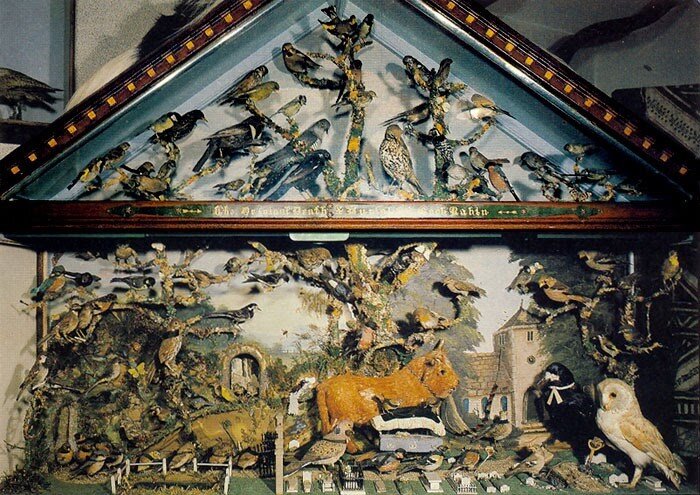

Potter accumulated quite the collection over his lifetime. One of his earlier pieces, which he started at the age of 19 and spent several years working on is “The Original Death & Burial of Cock Robin” (c. 1861). Inspired by the nursery rhyme “Who Killed Cock Robin,” this piece includes next to 98 specimens of British birds! In the same year, Potter opened his own museum to showcase his creations.

While Potter was clearly passionate, his taxidermy skills paled in comparison to say Ploucquet’s. However, where he lacked in precision, he made up for in his artistry, specifically in the minor details. One of his most famous pieces, which happens to be his last, is the “Kittens’ Wedding,” created in 1890.

This is one of my personal favourites – the whimsy of it all is truly engrossing. Your first reaction is probably either one of disgust or awe; however, you will be happy to know that Potter was not out murdering kittens for his pieces. On to the contrary, Potter only used previously deceased animals, which he received from a local farm.[2]

By the time Potter had died in 1914, his museum was coming to a stand-still. By the beginning of the twentieth century, people were no longer as interested in taxidermy and were beginning to raise questions about just how ethical taxidermy was. Nonetheless, to this day, Potter’s works are still discussed by those fascinated with this Victorian oddity.

Works Consulted

Amato, Sarah. “Dead Things: The Afterlives of Animals.” in Beastly Possessions: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture, 182-223. University of Toronto Press, 2015, doi:10.3138/j.ctt18dzs2z.

Burgan, Rebecca. ““Anthropomorphic Taxidermy: How Dead Rodents Became the Darlings of the Victorian Elite.” Atlas Obscura. 5 December 2014. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/anthropomorphic-taxidermy-how-dead-rodents-became-the-darlings-of-the-victorian-elite.

Henning, Michelle. “Anthropomorphic Taxidermy and the Death of Nature: The Curious Art of Hermann Ploucquet, Walter Potter, and Charles Waterton.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 35, no. 2, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp. 663-78, doi:10.1017/S1060150307051704.

Youdelman, Rachel. “Iconic Eccentricity: The Meaning of Victorian Novelty Taxidermy.” PSYART, vol. 21, University of Florida, 2017, pp. 38-68.

[1] Sarah Amato, “Dead Things: The Afterlives of Animals,” in Beastly Possessions: Animals in Victorian Consumer Culture (University of Toronto Press, 2015), 183.

[2] Rebecca Burgan, “Anthropomorphic Taxidermy: How Dead Rodents Became the Darlings of the Victorian Elite,” Atlas Obscura, 5 December 2014, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/anthropomorphic-taxidermy-how-dead-rodents-became-the-darlings-of-the-victorian-elite.