Emily Gartner

Over the last several years, a rite of passage for many young people in various circles has been to get a tattoo. Yes, permanent ink is something that has become fashionable once more in Western culture, with 22% of Canadians and 21% of Americans sporting at least one tattoo according to an Ipsos poll in 2012. This rate continues to rise, which is surprising to many because for a long time, tattoos have been associated with rebellion, deviance, and even criminality. To have a tattoo was uncommon and meant something very different early in the 20th century.

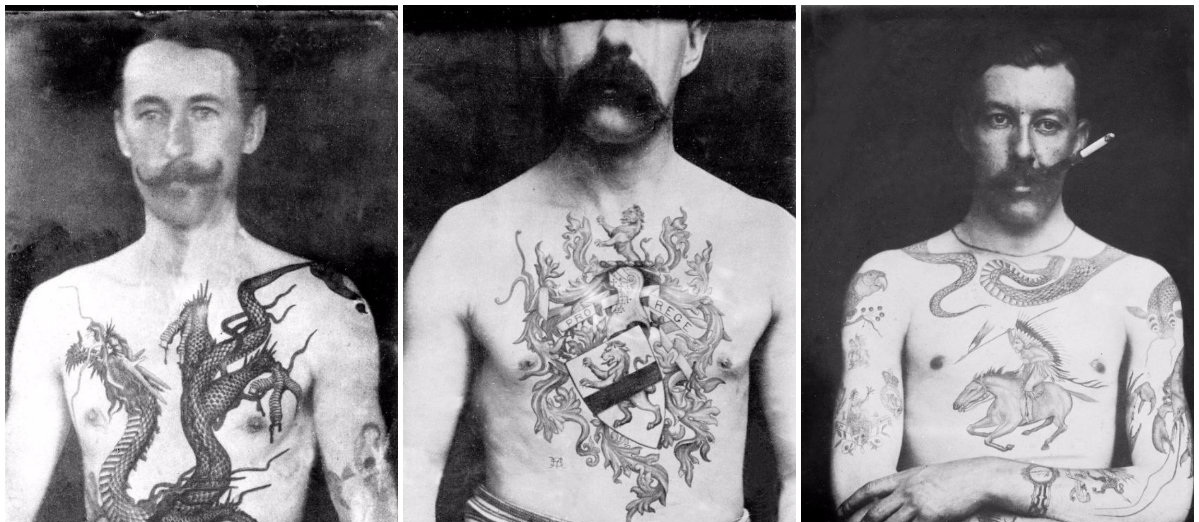

But this isn’t the first time that tattoos have gone from the shadows into the spot light; in the mid- to late-19th century, Victorians also dabbled in ink. Shocking as it may be to think of our straight-laced ancestors as having body art, it’s true.

Late 19th-early 20th century image of a man with a Japanese style tattoo.

Tattooing has existed in hundreds of cultures for thousands of years, being practiced for various reasons and using various methods. The oldest mummy in Europe, Otzi the Iceman, who was found in the Otzal Alps, has over 60 tattoos, dating back over 5000 years. For centuries, groups like the Celts, Greeks, and Romans practiced forms of permanent tattooing. Some used the practice to mark slaves or soldiers, while others cultural marks and symbols. When Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire, however, tattoos began to be classified as barbaric and were pushed out of fashion. For centuries after the traditions were lost, so tattoos as we know them today were actually brought back from somewhere else entirely.

Man with several tattoos, circa 1900

In the late 18th century, Captain James Cook was making his famous voyages to the Pacific and, while in the Polynesian Islands, he ran across a nation of people who were marked all over their body. He and his crew were reportedly fascinated by the practice, which they decided to call tattooing based on the word tatau that they locals used. When they returned to Europe, some of the sailors had tattoos and they had brought a Polynesian man with them who was also tattooed. People were shocked and intrigued, but outside of the British navy, most weren’t looking to get inked. This changed in the mid-19th century when, while visiting Jerusalem, the Prince of Wales received a tattoo of a cross as homage to the crusades.

Image of Captain James Cook

While the prince’s choice to get a tattoo was unusual, it was clearly a decision he was happy with, as he apparently had his two eldest sons, Albert, Duke of Clarence, and George (later George V), got tattoos while abroad in Japan. Both men reportedly had dragon designs tattooed on their arms by a famous artist. They added to their designs on their way back to England, stopping off in Jerusalem to have the artist that tattooed their father replicate his cross image on both of them.

With the introduction of tattoos by the British royal family, getting inked fell into fashion among the rich and noble of Europe. Soon the upper-class became very interested in obtaining tattoos of their own and, since the procedure was very expensive, only aristocrats and royalty were able to afford them. Among those inked in the mid- to late-1800s were several kings and emperors, including King Oscar of Sweden, Queen Olga of Greece , Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. The trend also included some unlikely characters, such as Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill’s mother. In fact, many women got tattoos, which were considered to be quite dainty and delicate.

Lady Randolph Churchill with her tattoo on her left arm, hidden beneath several bracelets.

For decades tattoos were in style, all the way through to the 20th century. But as prices were reduced and the availability increased, more people of a variety of backgrounds began to be inked. This growth in tattooing returned it to its reputation of being associated with lower-classes and deviance. It wasn’t helping that heavily tattooed individuals, such as John O’Reilly and Emma de Burgh, were often attractions at circuses and fairs. As time wore on, tattoos moved from royalty to rebels and were out of style once more. They remained on the down and out until their resurgence in the last 40 years.

Maud Wagner circa 1907

The story of the Victorian tattoo is like many fashion trends: it appeared, it rose, and it became popular with the rich, then with the masses, before fading into obscurity. Whether this will be the road of the modern tattoo is something we can’t know. For now, folks with tattoos everywhere can be rest assured, knowing that their ink has a history and quite a regal one at that.