The invention of the Christmas card was made possible by the invention of the Penny Post in 1840. To modern eyes, the motifs chosen for these cards may be a touch weird or even morbid at times. As these cards were the first of their kind, we see the early experimentation with different scenery and icons which did not survive into the 21st Century.

A Supernatural Encounter for Sir Hugh John Macdonald

Gabbing with Ghosts: The Fox Sisters and the Rise of Spiritualism

A Time of Many Hats

Emily Gartner

When thinking about the fashion of the late Victorian period, many people likely have elaborate gowns, fans, and jewelry cross their minds, as well as dapper suits and curled moustaches. Fashion of the 19th century is very distinct and clearly changed from one decade to another. But in the 1890’s there became one iconic staple of clothing that helped define the decade: the hats. Hats in the late Victorian-early Edwardian periods were diverse, fantastic, and unique. Both women and men saw changes in headwear that are interesting to explore. So let’s take a dive into the chapeaus that shaped two decades.

(Library and Archives Canada)

(Flickr Commons)

Headwear for women in the early 1800’s mainly consisted of deep bonnets with fine decoration on them. This changed throughout the 19th century, though, as women’s hats progressed from bonnets, getting smaller and moving further forward on the head. These changes were often prompted by changes in hair styles, and as they began to pile their locks on top of their heads, which changed where the hats had to cover. By the 1890s, hats were most commonly worn on the top of the head, varying in size and shape.

(Library and Archives Canada)

(Library and Archives Canada)

In an 1897 edition of The Glass of Fashion Up to Date, an American life and style magazine, there are several examples of the latest fashions for women, including several examples of hats. Many of the hats described were made with straw or a fabric, such as silk, and might be dyed different colours, like black, red, or green. The material often would set a colour theme for the hats and their decorations, which would be chosen to complement the colouring of the wearer.

Fashion plates (Library and Archives Canada)

Fashion plates (Library and Archives Canada)

These chapeaus were elaborately trimmed with ribbons, feathers, lace, buckles, and fantastic flower arrangements. They could include many different flowers, such as poppies, lavender sprigs, violets, and geraniums. Along with the flowers, some included aigrettes, which are stylish plums, made with feathers from egret birds, which were highly desirable. Others might include even have whole taxidermy birds or bird wings attached, which were often preserved using arsenic. These hats often had wide brims, with flowers circling the crown, creating almost a wreath on top of the head of the wearer. Others might have one or both sides of their hat with the brim turned up, and sometimes a sailor style would be worn, which had the front of the hat’s brim turned up, making almost a crown shape on their head.

(Library and Archives Canada)

(Library and Archives Canada)

Of course, for informal events or occasions, the hats selected might be far less elaborate. Some even bordered on masculine, with many women donning plain, straw boater hats, often with little more decoration than a simple hat band. In winter months, some worn plain toques or hats made from velvet or another fabric.

(Library and Archives Canada)

(Library and Archives Canada)

When it came to hats for men, who were expected to don a chapeau whenever they went outside, there were several styles that were popular. Top hats and tall hats dominated for evening occasions, with their flat tops and thin brims, but for day-to-day there was a bit more variety. Bowler or Derby hats became popular, with their rounded tops and brims. Homburgs were also on the rise, with their wide brims and dented tops, as were trilbys, which had thinner brims. Straw panama hats became increasingly popular and were good for warm days, along with woolen sporting caps. A cheaper alternative to both were fabric caps, or newsboy caps, often worn by members of the working class.

(Flickr Commons)

(Flickr Commons)

By the 1920s, the interest in big hats had largely died down. Women’s hats became smaller and more subdued, and men continued to ditch the top hat, and then other formal headwear. Nowadays we don’t see hats as the fashion “must” Victorians did, but the images that were created of beautiful and fantastic chapeaus will continue to be iconic representation of the by gone times of the 1890’s and 1900’s.

BONUS- Author’s favourite hat photographs:

(Library and Archives Canada)

(Library and Archives Canada)

(Flickr Commons)

Written in Ink: the Victorian Tattoo Craze

Emily Gartner

Over the last several years, a rite of passage for many young people in various circles has been to get a tattoo. Yes, permanent ink is something that has become fashionable once more in Western culture, with 22% of Canadians and 21% of Americans sporting at least one tattoo according to an Ipsos poll in 2012. This rate continues to rise, which is surprising to many because for a long time, tattoos have been associated with rebellion, deviance, and even criminality. To have a tattoo was uncommon and meant something very different early in the 20th century.

But this isn’t the first time that tattoos have gone from the shadows into the spot light; in the mid- to late-19th century, Victorians also dabbled in ink. Shocking as it may be to think of our straight-laced ancestors as having body art, it’s true.

Late 19th-early 20th century image of a man with a Japanese style tattoo.

Tattooing has existed in hundreds of cultures for thousands of years, being practiced for various reasons and using various methods. The oldest mummy in Europe, Otzi the Iceman, who was found in the Otzal Alps, has over 60 tattoos, dating back over 5000 years. For centuries, groups like the Celts, Greeks, and Romans practiced forms of permanent tattooing. Some used the practice to mark slaves or soldiers, while others cultural marks and symbols. When Christianity became the religion of the Roman Empire, however, tattoos began to be classified as barbaric and were pushed out of fashion. For centuries after the traditions were lost, so tattoos as we know them today were actually brought back from somewhere else entirely.

Man with several tattoos, circa 1900

In the late 18th century, Captain James Cook was making his famous voyages to the Pacific and, while in the Polynesian Islands, he ran across a nation of people who were marked all over their body. He and his crew were reportedly fascinated by the practice, which they decided to call tattooing based on the word tatau that they locals used. When they returned to Europe, some of the sailors had tattoos and they had brought a Polynesian man with them who was also tattooed. People were shocked and intrigued, but outside of the British navy, most weren’t looking to get inked. This changed in the mid-19th century when, while visiting Jerusalem, the Prince of Wales received a tattoo of a cross as homage to the crusades.

Image of Captain James Cook

While the prince’s choice to get a tattoo was unusual, it was clearly a decision he was happy with, as he apparently had his two eldest sons, Albert, Duke of Clarence, and George (later George V), got tattoos while abroad in Japan. Both men reportedly had dragon designs tattooed on their arms by a famous artist. They added to their designs on their way back to England, stopping off in Jerusalem to have the artist that tattooed their father replicate his cross image on both of them.

With the introduction of tattoos by the British royal family, getting inked fell into fashion among the rich and noble of Europe. Soon the upper-class became very interested in obtaining tattoos of their own and, since the procedure was very expensive, only aristocrats and royalty were able to afford them. Among those inked in the mid- to late-1800s were several kings and emperors, including King Oscar of Sweden, Queen Olga of Greece , Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Grand Duke Alexis of Russia. The trend also included some unlikely characters, such as Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill’s mother. In fact, many women got tattoos, which were considered to be quite dainty and delicate.

Lady Randolph Churchill with her tattoo on her left arm, hidden beneath several bracelets.

For decades tattoos were in style, all the way through to the 20th century. But as prices were reduced and the availability increased, more people of a variety of backgrounds began to be inked. This growth in tattooing returned it to its reputation of being associated with lower-classes and deviance. It wasn’t helping that heavily tattooed individuals, such as John O’Reilly and Emma de Burgh, were often attractions at circuses and fairs. As time wore on, tattoos moved from royalty to rebels and were out of style once more. They remained on the down and out until their resurgence in the last 40 years.

Maud Wagner circa 1907

The story of the Victorian tattoo is like many fashion trends: it appeared, it rose, and it became popular with the rich, then with the masses, before fading into obscurity. Whether this will be the road of the modern tattoo is something we can’t know. For now, folks with tattoos everywhere can be rest assured, knowing that their ink has a history and quite a regal one at that.

Cabinets of Curiosities: Wondrously Wild Wunderkammers

Emily Gartner

In the earliest days of the museum, starting in the 16th and 17th centuries, there were no grand, national galleries, interactive public exhibits, or (sadly) heritage homes to visit. Back then, the museum was nothing more than a box in the homes of the influential. A cabinet filled with things that were exotic and exemplary of the owner’s power and prestige. People would show off these wunderkammers, or cabinets of wonders, to their guest, and have cabinet makers create and paint cupboards, drawers, even whole theatres for their growing collections. These cabinets grew in popularity and reached the point where the rich and noble were not alone; middle class merchants were expected to also keep and curate their own, more modest, cabinets. All were unique and, while they do follow the modern museum idea of preserving and displaying things for visitors to look at, they are very different from our museums today.

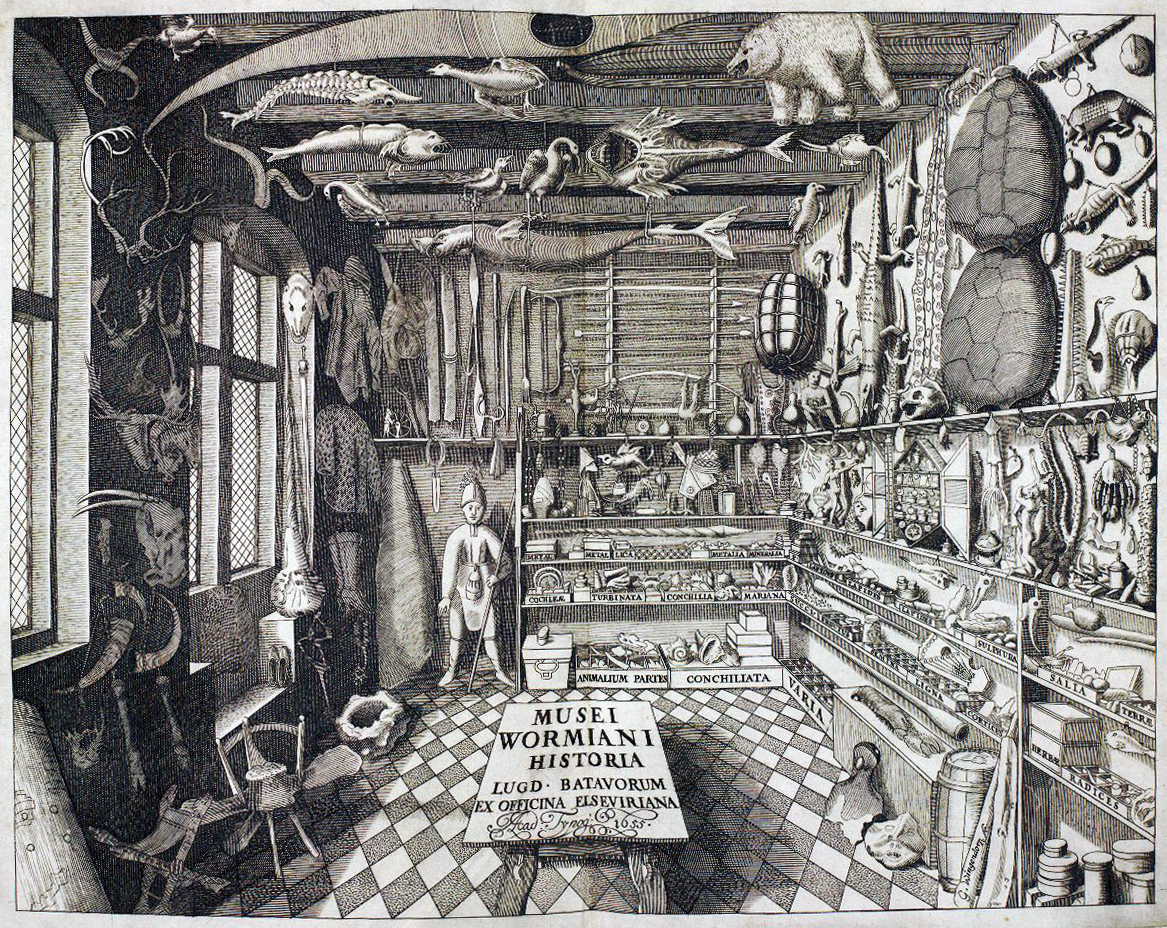

"Musei Wormiani Historia", the frontispiece from the Museum Wormianum depicting Ole Worm's cabinet of curiosities.

When we think of a museum or exhibit, generally there is some sort of subject theme to them, which their exhibits reflect. For example, Dalnavert is a Victorian heritage home. Its theme is history, specifically Victorian Canadian history. The curator is not likely to decide to suddenly display a lion skull or a Roman dagger because, as cool as they both are, they don’t really fit with the museum’s mandate. Cabinets of curiosities, however, were different. They were meant to include all sorts of different objects which might have nothing in common except they were all cool, rare, or expensive. This wasn’t just to show off the owners wealth (although they did that too), but was to create a sort of image of the world through the eyes of the person curating the cabinet. To make a good cabinet, one truly representative of the whole world, the owner had to include objects that were from the natural world, relics from the ancient world, art, exotic artefacts, and even mystical or magical things. The arrangement of the collection was entirely up to the owner. So they might include objects representative of the natural world, including plants, animals, and minerals alongside art or artefacts from different parts of history or the world. A lot of them were arranged based on symmetry of colour or size. Or they could arrange them to tell a story, either of the family or person who owned it, or maybe of the universe as they knew it.

Pitt rivers Museum, Oxford

Photographer: Danny Chapman, Flickr

Cabinets fell out of fashion with the introduction of the modern public museum. By the Victorian period, while families might have collections, cabinets were of less interest. Today, cabinets of curiosities exist more as a novelty than as a social status indicator or as a modern museum. Some do still exist as museums, like the Pitt Rivers museum in Oxford, which continues to display its artefacts cabinet-style, with lots on display, but with little labelling or clear theme. Part of the appeal of the place is that it exists as an example, a snapshot, of what a museum based on a cabinet would have looked like. Other museums, like the British or Ashmolean Museums have cabinet of curiosity roots, with their collections initiated by a personal cabinet, but have since evolved into more modern institutions. This was often done to make their institutions more accessible or better suited to house their collections, but in the process they did away with how their collections might have been laid out when they were first obtained.

Some people have also made their own modern versions of the cabinets. They are a bit different now, though, as they have become associated with the weird or creepy, and are now often used for shock effect. For instance, in London there is the Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, which is full of artefacts many of which you can buy, including several skulls, taxidermy, and dolls, all of which vary from the bizarre to the grotesque. This type of museum is not as much a historic example of a cabinet of curiosities as much as a modern interpretation of the style. Cabinets during the Renaissance would not have been seen as creepy, but as quite fashionable (despite the skulls). Still, the idea of a space full to bursting with items of wonder is very true to the original cabinet trend’s hallmarks.

Viktor Wynd in front of his museum.

Photographer: Oskar Proctor

Over the centuries, our perception of what is and is not a museum has changed. Cabinets of curiosities have gone form the only game in town to being representative of the fancies and fantasies of our ancestors. Yet we still, as people, continue to collect and display things in our homes, some natural and others man-made. So take a look around your house and see: could you build a cabinet of your own personal wonders?

Camping in Victorian Times

Emily Gartner

For many Canadian families, no summer is complete without a family camping trip; whether it’s at a local or national park, a cabin, or in the backwoods, Canada is full of great spots to camp and people who love to go discover them. But it wasn’t always this popular. Before the 1870’s, there was little interest in camping. Most people couldn’t afford to take time off work and travel and those who could were more likely to want to relax in a hotel than the forest floor. But in the late-Victorian period, several factors led to the popularisation of camping among the upper and middle-classes. Thus, camp grounds and summer homes became populated with families, hoping to get away from it all in the summer months.

Following the industrial revolution, many Victorians saw their lives becoming filled with modern comforts and amenities, which made it difficult to try new things and feel connected to the natural world. Many viewed this as an issue and began to fanaticise about living off the land, away from urban life. At the same time, there were many books and publications telling romantic and exciting stories about the great American and Canadian frontiers in the West and all of the opportunities that they offered. These books captured imaginations with stories of cowboys and gold miners, explorers and warriors, all seeking a life on the range. As people read them they would start to desire to go and enjoy the great outdoors with their own friends and families. And many did just that.

Campers and game at Comfort Point, Columbus Camp, Muskoka Lakes, Ont., 1887. (Library and Archives Canada)

Going camping often entailed many weeks of bringing only the barest of necessities in an attempt to prove that they could easily live off the land. People slept of beds of pine boughs and washed up in rivers and lakes. They observed wild animals and ate many of them too. They hiked, biked, and canoed with abandon, adventuring and exploring as much as they could.

This getting back to nature mean that many families left their servants behind and did all of the chores and work themselves. This led to common role-reversal, as husbands took up housework, like dish and clothes washing, which normally would be the domain of their wives or lady servants. Meanwhile, women often chose to wear men’s clothes and pants rather than long dresses, as they were more practical, which was something that would have been socially unacceptable back in their hometowns.

Boy Scout camp, Lambton, Ontario (Library and Archives Canada)

Not all families opted to go without any servants or assistance while camping; many did hire guides, who were mostly local men who knew the lay of the land. These guides would help them understand how to set up and look after their campsites and show them around. Many were also engaged to cook and clean for the families, so that the campers didn’t have to do it for themselves.

As the concept of camping and living off the land became popular many people sought for more permanent and organised experiences when tackling an outdoors adventure, which led to the establishment of places that provided camp programming, particularly for youth. The YMCA was the first to respond to the desire for summer camps in North America, opening their first camps in the 1880’s and ‘90’s for young adults to attend during their holidays. Other camps run by different churches and community organisations soon followed, offering programs that included activities like canoeing, tenting, and sports for their eager campers. This style of camp continues to exist in various forms and is still quite popular today.

Around the same time, adventure magazines and journals became popular. Boys would read these along with adventure novels that would make camping and hiking exciting and glamourous, causing many to seek to travel the world and live off the land. These books continued to be popular following the end of the Victorian era in 1901, with many becoming best sellers and encouraging youth to get outside and embrace nature. One especially popular publication was Scouting for Boys, written by Lord Robert Baden-Powell, who was a veteran of the Boer Wars. This book prompted the creation of the Scouting Movement, which still exists today as the largest youth organisation world-wide. It also directly influenced the creation of the Guide movement, which was developed as an organisation specifically geared towards young women. Both teach outdoor skills and use camping as a method of delivering their core messages and values.

Boy Scouts and Girl Guides in front of Court House (Library and Archives Canada)

Since the Victorian period, camping has become a traditional pastime for many families in Canada, who still use it as a chance to get away from city life and connect with nature. While many of the things we use for camping have changed, right along with the time, camping can still be a lot of fun and a great way to spend your holidays.

The Indian Women who Raised British Children

Above is a Podcast of the writer interviewing Dr. Raminder Saini about ayahs and subjecthood in the British Empire. The podcast was made for a class exercise to help students like our writer Morgan Marshall discuss the scholarship and content of their research. Take a listen and read on!

The Indian Women who Raised British Children

by Morgan Marshall

“ The ayahs of the present century, more akin to serfs than the domestic servants to which we are ordinarily accustomed”. - A.C Marshall in the 1922 Quiver Magazine.

Ayahs are single Indian women who worked as both domestic servants and nannies for British children in the 19th century. Ayahs worked in India for British families as well as aboard ships that travelled between Europe and India. In the 1922 edition of the Quiver, the author draws comparison between ayahs and serfs; instead of being bound to the land, ayahs were bound to British children. Although, tied to these children, they weren’t slave-like laborers, but rather motherly figures travelling colonial “water highways” with British families as a career. Read on to find out more about these Indian women who raised British children.

In India, ayahs provided expertise to their memsahib (the British mother they worked for) about how to survive and thrive in the colonial environment. They provided complete childcare for the white children, including feeding, bathing, clothing, and playing with the children. Often spending more time with their ayah than their biological parents. They also provided domestic and medical advice for the memsahib. For example, ayahs constantly stressed the use of wet nurses, this ensured the baby would get an abundant supply of nutrient milk and the memsahib would not exhaust herself. This was essential as the child mortality rates were double that of Europe.

On ships, ayahs were in charge of complete childcare, cleaning, laundry, looking after the baggage, and memsahib. Some even qualified as nurses and sailors. Antony Pareira, for example, was an experienced ayah that traveled between Britain and India 54 times and to Holland once. She was a young mother looking for adventure, finding her “life’s calling” by caring for children and travelling the “water highways” of the British Empire. This brought Indian women freedom to travel and explore the world, while earning decent money to provide for her own children back home.

What makes ayahs’ work so interesting is their inevitably close relationship with British children. This broke racial boundaries because ayahs were raising white children, while advising white mothers. Mary Sherwood, for example, was a Victorian mother living in India who wrote in her journal that her children “carry in their hearts the Ayah’s laughter and tears”. This relationship crossed racial and social boundaries, creating an ambivalent space in the British family. Many children became more familiar with Indian languages and culture because of the close relationship they shared with their ayah. So close, that when Mary Sherwood’s infant suddenly died, she heard her ayah “un-feignedly” weeping for “her boy”.

Life in Britain wasn’t always easy for foreign workers. The Ayahs’ Home was established to house, feed, clothe, and protect ayahs in England. Founded in 1897 by Mr. and Mrs. Rogers, the Home had 30 rooms and every year over 100 ayahs stayed there. The women were provided with a safe place, which offered Indian food, familiar languages, and culture. This institution was not only a place of refuge for Indian women but also doubled as a Victorian employment agency, helping Indian women find employment for the journey home. In 1900, the Rogers could no longer run the home, it then came under the control of Christian missionaries, as they saw the opportunity to help foreign women in need.

What is most fascinating about ayahs is how little information there is on them! I was astonished that historians knew so little about such courageous women that broke gender, race and class boundaries throughout the centuries. Their close relationship with British children allowed these women into important positions at the heart of a Victorian household. Whether their employers wanted or not, ayahs had a lasting impact on future British generations. Impacts that were undesirable to the British, as Victorians believed children were being “culturally contaminated” by a “weaker race”. However, this did not cease the employment of ayahs, their expertise with children was undeniably excellent.

About this blog writer: Morgan Marshall is an undergraduate student studying History and Art History at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus.