The Red River Resistance was an initiative spearheaded by Louis Riel and the Red River Colony, most of the members being Métis. The Resistance disagreed with the Hudson’s Bay Company selling Rupert’s Land to the Canadian Government because it was not theirs (HBC’s) to sell. This blog post looks at Hugh John Macdonald’s involvement in both the Wolseley Expedition of 1870 and the North-West Rebellion of 1885, which set out to dominate the Métis and their Indigenous and European heritage.

The Indian Women who Raised British Children

Above is a Podcast of the writer interviewing Dr. Raminder Saini about ayahs and subjecthood in the British Empire. The podcast was made for a class exercise to help students like our writer Morgan Marshall discuss the scholarship and content of their research. Take a listen and read on!

The Indian Women who Raised British Children

by Morgan Marshall

“ The ayahs of the present century, more akin to serfs than the domestic servants to which we are ordinarily accustomed”. - A.C Marshall in the 1922 Quiver Magazine.

Ayahs are single Indian women who worked as both domestic servants and nannies for British children in the 19th century. Ayahs worked in India for British families as well as aboard ships that travelled between Europe and India. In the 1922 edition of the Quiver, the author draws comparison between ayahs and serfs; instead of being bound to the land, ayahs were bound to British children. Although, tied to these children, they weren’t slave-like laborers, but rather motherly figures travelling colonial “water highways” with British families as a career. Read on to find out more about these Indian women who raised British children.

In India, ayahs provided expertise to their memsahib (the British mother they worked for) about how to survive and thrive in the colonial environment. They provided complete childcare for the white children, including feeding, bathing, clothing, and playing with the children. Often spending more time with their ayah than their biological parents. They also provided domestic and medical advice for the memsahib. For example, ayahs constantly stressed the use of wet nurses, this ensured the baby would get an abundant supply of nutrient milk and the memsahib would not exhaust herself. This was essential as the child mortality rates were double that of Europe.

On ships, ayahs were in charge of complete childcare, cleaning, laundry, looking after the baggage, and memsahib. Some even qualified as nurses and sailors. Antony Pareira, for example, was an experienced ayah that traveled between Britain and India 54 times and to Holland once. She was a young mother looking for adventure, finding her “life’s calling” by caring for children and travelling the “water highways” of the British Empire. This brought Indian women freedom to travel and explore the world, while earning decent money to provide for her own children back home.

What makes ayahs’ work so interesting is their inevitably close relationship with British children. This broke racial boundaries because ayahs were raising white children, while advising white mothers. Mary Sherwood, for example, was a Victorian mother living in India who wrote in her journal that her children “carry in their hearts the Ayah’s laughter and tears”. This relationship crossed racial and social boundaries, creating an ambivalent space in the British family. Many children became more familiar with Indian languages and culture because of the close relationship they shared with their ayah. So close, that when Mary Sherwood’s infant suddenly died, she heard her ayah “un-feignedly” weeping for “her boy”.

Life in Britain wasn’t always easy for foreign workers. The Ayahs’ Home was established to house, feed, clothe, and protect ayahs in England. Founded in 1897 by Mr. and Mrs. Rogers, the Home had 30 rooms and every year over 100 ayahs stayed there. The women were provided with a safe place, which offered Indian food, familiar languages, and culture. This institution was not only a place of refuge for Indian women but also doubled as a Victorian employment agency, helping Indian women find employment for the journey home. In 1900, the Rogers could no longer run the home, it then came under the control of Christian missionaries, as they saw the opportunity to help foreign women in need.

What is most fascinating about ayahs is how little information there is on them! I was astonished that historians knew so little about such courageous women that broke gender, race and class boundaries throughout the centuries. Their close relationship with British children allowed these women into important positions at the heart of a Victorian household. Whether their employers wanted or not, ayahs had a lasting impact on future British generations. Impacts that were undesirable to the British, as Victorians believed children were being “culturally contaminated” by a “weaker race”. However, this did not cease the employment of ayahs, their expertise with children was undeniably excellent.

About this blog writer: Morgan Marshall is an undergraduate student studying History and Art History at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus.

Indian Labourers in a Victorian City

“The Evil and How Occasioned”: Caring for Migrants in a Victorian City

with Dr. Raminder Saini

Sunday, March 24 @ 1:30

$15 Admission | $12 Members

“Found dead!” Who? Where? Has he no friends? How did he die? …“We don’t know.”

Excerpt from Joseph Salter, The Asiatic in England (1873).

So writes Joseph Salter, a missionary who worked in London’s East End. In his first memoir, The Asiatic in England (1873), Salter reflected on the condition of labouring Indians in early 19th century London.

In the early 1800s, thousands of Indian labourers were moving through the port of London. Lascars (Indian sailors), servants, and ayahs (nannies) signed contracts in which they agreed to work on board ships headed to English ports. On landing in London, though, too many discovered that guaranteed return passages to their port of origin were merely empty promises. Some weren’t even paid their wages. Not prepared for a prolonged stay in London, these labourers found themselves without food, shelter, or a way home.

The issues of distressed Indian labourers, especially lascars, increased after the 1830s. For middle-class Victorians in particular, the presence of distressed Indians was alarming: how could there be distressed colonial subjects in the metropole? What did their condition say about Britain? What did this say about Victorians as good, Christians who were trying to “bring civilization” to the peoples they colonized?

To tackle the problem of increasing and abandoned destitute lascars, members from missionary organizations established the Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans, and South Sea Islanders. This lodging house opened its doors in the spring of 1857 after a year of construction. Initially, the institute was formed to provide a solution to lascars who were not adequately housed by the East India Company. As the administrators began their work, though, they realized that there were other labourers in similar conditions of distress. The Strangers’ Home thus became a space through which Victorians could provide “help” to working-class Indians.

Sketch of the Strangers’ Home for Asiatics, Africans, and South Sea Islanders in Joseph Salter, The Asiatic in England (1873).

Not everyone wanted to be helped though. For example: Abdul Rehmon was from Bombay. He had been living in London for twenty years when Salter discovered him. Rehmon had begun earning a living by sweeping streets, but then got involved in a lucrative business in Bluegate-fields where he “pandered to the vices of his countrymen when they arrived in England” – in other words, he owned an opium den. Rehmon was perfectly content with the life that he led in the heart of the empire…

To find out more about the Strangers’ Home and Victorians’ idea of “helping”, check out this Sunday’s lecture with Dalnavert’s very own Intern Curator, Rammy Saini! More details on her talk can be found here.

Soap, Race, and Cleanliness

Raminder Saini

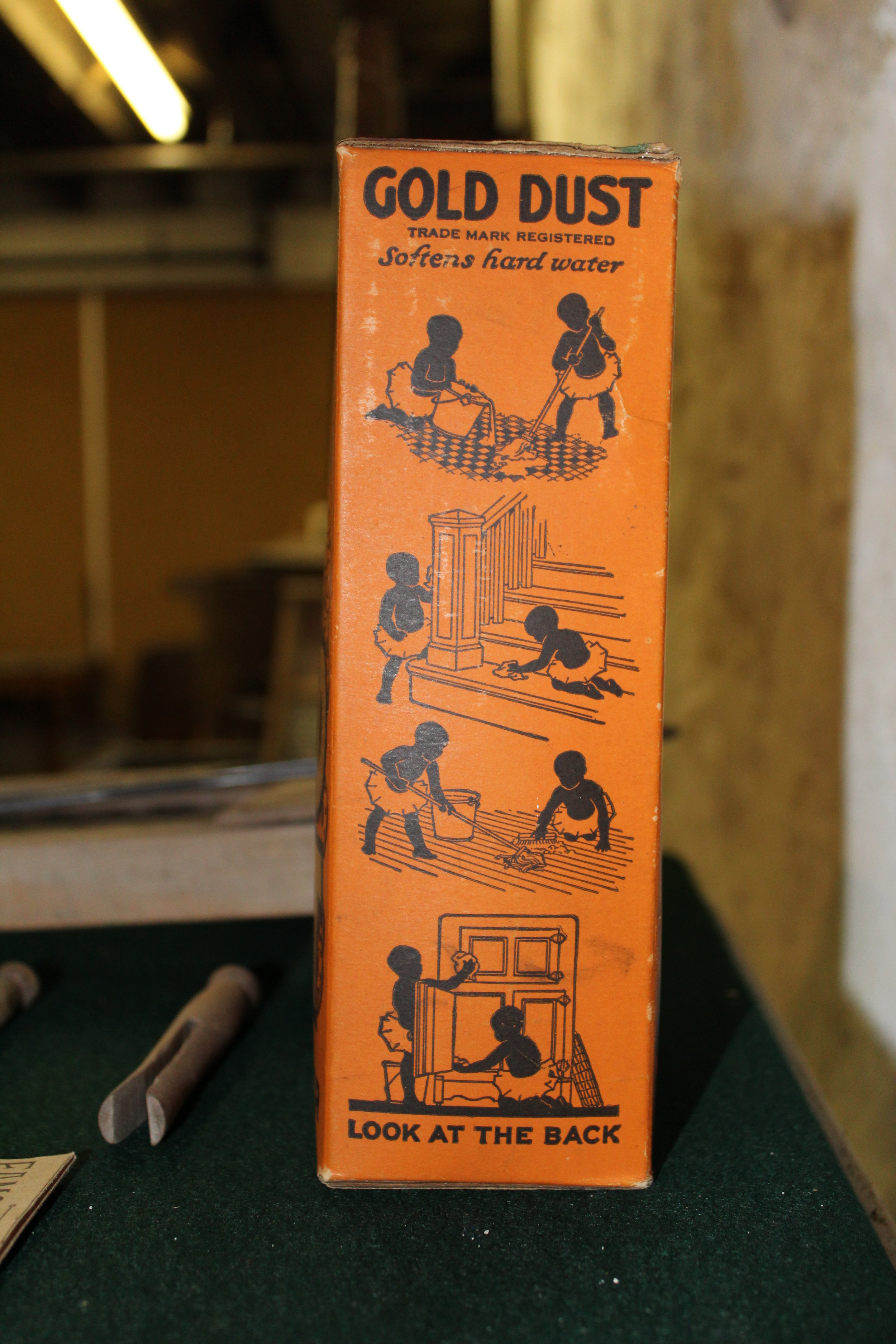

“The Fairbank ‘Darky Twins’ on the ‘Gold Dust’ package are as familiar to the average housewife as the face of the family clock.” - Maine Farmer, April 1, 1897

The “Gold Dust Twins” were a pair of African American caricatures displayed on a popular box of washing powder from the 1880s to the early 1900s. These twins, grotesquely referred to as “the Darky Twins” by the Maine Farmer in 1897, symbolized racial attitudes that Victorians often held at the time. But who were the twins? And why should we be talking about washing powder?

Soap in the late 1800s represented more than the physical aspect of “getting clean.” The Victorian idea of cleanliness became tied to the concept of imperialism and Victorian superiority. Many Victorians, as it is well known, felt superior to the people they colonized (from Africans and Indians to Indigenous communities in Canada). Victorians also came to associate whiteness with cleanliness and blackness with dirtiness – a notion co-opted rather successfully by soap manufacturers in racialized advertisements. Take for example an advertisement for Pears’ Soap:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pears-1884.jpg

This ad plays on the themes of imperialism and racial stereotypes that were common to the Victorian era. In the image to the left you have an African child being placed into a tub and about to be washed with Pears’ Soap, which is held in the hand of the white child. In the next image, the African child no longer has black skin. The child has been scrubbed clean of its “dirtiness” and has thus been “civilized” (or so it is implied). As the ad reads, “I have found PEARS’ SOAP matchless for the Hands and Complexion.” This rather horrific advertisement plays on the Victorian mission to “civilize” colonized peoples.

At Dalnavert, the laundry soap on display is “Gold Dust Washing Powder.” “Gold Dust” was an American soap, manufactured by the N.K. Fairbank Company in Chicago. This company had factories in both North America and Europe. According to The New York Times (March 17, 1895), this soap was the leading washing powder at the time. It is only fitting then that a box of it lies in the laundry room at Dalnavert.

More of an all-purpose cleaner than strictly laundry soap, “Gold Dust” was meant to make the life of a housewife easier. How? Well, the sides of the box depict two African American twins who appear to happily be doing household chores. The twins, incidentally, represent the power or strength of two cleaners in one, efficient washing powder. For middle-class Victorians, the less work a housewife could do with her hands, the more time she could devote to leisure activities that would better allow her to mimic the lifestyle of the upper classes. As it stood, one main division between middle and upper class families was that the upper classes never had to sully their hands with simple household chores—that’s what servants were for!

This image, though, of African American twins happily doing housework is yet another expression of contemporary racial attitudes. Since the washing powder is American, it is a different kind of advertising from that of the Pears’ Soap Company. Arguably, the image of the “Gold Dust” twins align better with slavery in America and the use of Africans for domestic labor than simply Victorian ideas of cleanliness and civilization. But regardless of the difference, racial soap advertisements enforced widespread ideas of late-nineteenth century imperial and racial superiority. Worse, people literally bought into these stereotypes by buying products from N.K. Fairbanks and Pears. Accordingly, the soap on display at Dalnavert goes beyond merely displaying a common household item and instead showcases a connection to the larger forces at play in both North America and the British Empire when it came to cleanliness.