Welcome to the first installment of the In A Sense series. These blogposts are linked with the In A Sense tactile exhibit currently on display in the Dalnavert Museum Visitor’s Center. For additional resources, follow the links at the bottom of this post. To see the full exhibit, drop by the museum or book a tour through our website.

Warning: Briefly discusses the eugenics movement and the dehumanization of persons in the deaf community and/or those with disabilities during the Victorian Era.

Sound is a constant sensation. Even when one is in a quiet space, the body recognizes vibrations in the air. Sometimes, sound is all in the background – the sirens, the birds, the elevator music – while at other times, sound is the focus such as conversations, the patter of rain, or during performances. Though Victorians did not have the constant access to personalized music or podcasts that we do today, their bodies still recognized the constantly loud world around them. The sound of carts and street performers would echo along main roads while houses would creak and moan with wind and water boilers. After the working day, families and communities would often come together to tell stories or listen to one another play music. New technologies helped broaden this listening experience including recordings from phonographs (and similar devices) and toys for children such as talking dolls.

Included among new auditory inventions was the telephone, which irreversibly revolutionized modern communication. The rise of this auditory device not only meant changes for industry and personal messaging but shifted perceptions around people in the deaf community. Jennifer Esmail, author of Reading Victorian Deafness: Signs and Sounds in Victorian Literature and Culture, noted that the telephone “ushered in a new age of human communication that largely excluded deaf people for almost a century.” This exclusion was linked with arguments between groups who had different ideas around the humanity of deaf and disabled individuals. There were strong opinions from people like Alexander Graham Bell who believed in oral education and eugenics, (i.e., not allowing deaf people to use sign language or bear children with one another) ideologies which furthered the Darwinian argument that language – specifically spoken language in this case – is the separating factor between humans and animals. This made it extremely difficult for manual education (education which used sign language and other inclusive teaching methods) to gain ground because sign language was not always considered a form of language in its own right. This also had racist connotations that included the implied inferiority of students in North America using sign language(s) in residential schools.

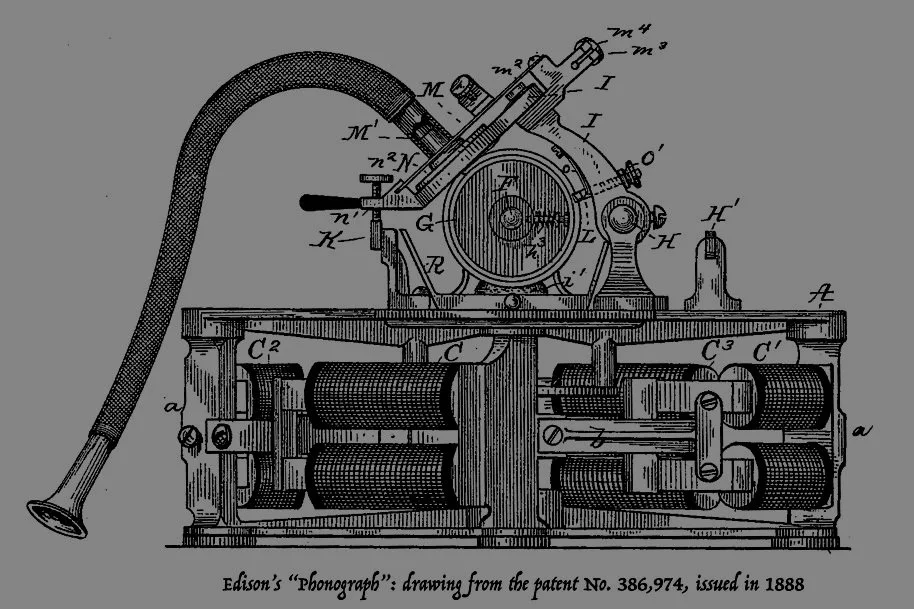

With this being said, the Victorian era is still viewed as a major time of auditory invention and understanding. Music halls and saloons were coming to the fore with new operas such as those by Gilbert & Sullivan and performing a cappella groups known as “glees” gracing stages across the globe. Performances could now be recorded using phonautographs (a device created in the 1860s by Édouard Léon Scott de Martinville which recorded sounds by producing a visual representation of sound waves with a bristle brush and soot), phonographs and graphophones, (recording devices by Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell from the 1870s-1880s which used spinning cylinders to retransmit sounds) and later gramophones (recording devices which used discs to retransmit sound). Queen Victoria herself received a voice recording session in 1888 where she greeted her subjects through a cylinder recording.

The Victorian soundscape was not limited to recordings or performances. Because so many people worked out of their homes, street noise had an impact on daily life. Regulations on street noise in the UK, including restrictions for organ grinders and other musicians, began in the 1840s and indicated a separation from people who worked on the streets and those who found careers in their homes. Especially in crowded cities like London, people considered their homes a reprieve from the outside world and did not take kindly to those who audibly invaded that space. By the 1890s, however, the scorn for street noise transitioned to a type of nostalgia, as indicated through poetry and art of the time. As John M. Picker concluded in his essay The Soundproof Study: Victorian Professionals, Work Space, and Urban Noise,

“Once repellent, street music now attracted those who might hear in its strains the sound of their own struggles or those of their age. . . Artists and writers in vocations once opposed to and imperiled by street music ultimately appropriated and aestheticized it as a voice and symbol . . . city noise no longer worked against art, as Victorians had perceived it, but, ironically, within it.”

Postcard of Winnipeg Main Street, 1888. Courtesy of the Winnipeg Archive.

Articles and Books:

“Books Without Ink” https://www.bookswithoutink.com/

Dash, Mike. “In Search of Queen Victoria’s Voice” Smithsonian. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/in-search-of-queen-victorias-voice-98809025/

Esmail, Jennifer. Reading Victorian Deafness: Signs and Sounds in Victorian Literature and Culture Review from the Wilkie Collins Society. https://wilkiecollinssociety.org/reading-victorian-deafness-signs-and-sounds-in-victorian-literature-and-culture/

“Music And Musicians In The Victorian Era” http://victorian-era.org/music-and-musician-in-the-victorian-era.html

Parkins, Wendy “Trust your senses? An Introduction to the Victorian Sensorium” Sensory Studies. https://www.sensorystudies.org/sensorial-investigations/trust-your-senses-an-introduction-to-the-victorian-sensorium/

Picker, John M. The Soundproof Study: Victorian Professionals, Work Space, and Urban Noise 1999, https://lit.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/jPicker-3Soundproof.pdf

“Sounds of the 1860s: listen to the earliest recordings known” Classic FM. https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/oldest-recordings/

Recordings:

Library of Congress 1800 – 1899: https://www.loc.gov/audio/?all=true&c=150&dates=1800/1899&fa=subject:music%7Caccess-restricted:false%7Csubject:19th+century&sb=date

Victorian Street Sounds: https://sounds.bl.uk/Environment/Sound-effects/027M-1CD0126081X2-0100V0

Queen Victoria, 1888: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/in-search-of-queen-victorias-voice-98809025/

October 5, 1888 Dinner Party Introducing the Phonigraph: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ebDdwcsrB4U

For more go to https://www.friendsofdalnavert.ca/sound